I. Introduction

The main Shakespeare’s purpose is to sustain the divine providence

and restore the peace and order. The path to achieve this is primarily by

drawing human beings to perfection. In the quest for mastering human characters

with all their good and bad features, Shakespeare often struggles to balance

between good and evil.

Furthermore, the common, ordinary and yet witty and wise

conversations, tend to produce the sense of reality. When all these elements

are combined we get a living character. But being a living character means

coming to terms with all human desires and ways to achieve them. People are

hardly ever sure what really want to achieve. And that is the human feature.

Questioning our decisions and actions is what makes us weak. Particularly this

issue, the phenomenon called conscience, will be discussed regarding the

consequences of it through the prism of the main characters’ attitudes in the

plays Hamlet, Richard III and Macbeth.

II. Short overview of the male characters in these plays

In the play Hamlet the

Prince of Denmark, the central issue is Hamlet’s tendency to perform the

good on Earth. Thus two conflicts appear. On the one hand is his desire to

fulfil the ghost’s demand for revenge. On the other, is his awareness that it

would involve him in evil himself. In fact he is tormented by his conscience

whenever he decides to take action.

The play Macbeth

is a study of the human potential for evil. It illustrates the concept

of the downfall of a human being. Macbeth comes to a point where the aim to be

crowned is achieved. Also he has met his wife’s expectations in proving his

masculinity, but all these to the expense of his tranquillity. Here the

apparitions and madness point to the power of conscience.

Similarly, in the

play Richard III, main character’s

immense capacity for crime is a final, climactic instance of the disruptive

ambitions to win the kingdom. Richard exemplifies something larger than his own

fascinating personality and hubris. What is stronger than him is his conscience,

again as in Macbeth, taking the form of ghosts and apparitions that does not

even allow him to sleep.

III. Common characteristics

What all these characters have in common are certainly

temptations of different kinds that drive them into sin. The tendency to be

sinners and that also stands for cowards, is deep in the origins of their

nature. In fact particularly that is what makes humans be humans. Many scholars

have discussed particularly on this topic and the standings vary a lot.

Coleridge identifies the conscience issue with the Shakespeare’s “deep and

accurate science in mental philosophy”(Larque). Furthermore in another of his

lectures, Coleridge notes that “we are always loth to suppose that the cause of

defective apprehension is in ourselves, the mystery has been too commonly

explained ... by the capricious and irregular genius of Shakespeare.”(Foakes 75).

Others believe that consciousness is the vehicle that is driven by good

intentions, and can end up maliciously when not being managed moderately. But

it is the conscience that appears as a consequence of the struggle to play on

the safest side by maintaining both the religion and personal beliefs. In his

essay “On consciousness” Montaigne tries to define it “Nevertheless

amongst the honest men that follow, of those I say divers are seene, whome

passion thrusts out of the bounds of reason, and often forceth them to take and

follow unjust, violent and rash counsels.” (Florio 384).

IV. Different approaches

Another scholar, Harold Bloom, perceives Shakespeare “to have invented the human by writing

characters that change, struggling with their own nihilism in the face of

mortal finitude. He argues that Shakespeare invented characters whose inwardness

or individuated conscience is unprecedented in literary history.”(Bloom).

Shakespeare achieved a fundamental break with his predecessors. We cannot

merely say Shakespeare’s characters are true likenesses of people. Shakespeare

did not imitate humanity already simply in existence; rather, in a real sense,

he invented the human as we now understand it. The nihilizing conscience of

Shakespeare’s major characters, mark them as beings who evade

contextualization.

But mainly the most accurate

definition on conscience is given by Ovid:

“As each mans minde is

guiltie, so doth he

Inlie breed hope and feare,

as his deeds be.” (Ovid. Fast. i. 485.)

Regarding this,

we will discuss that all our deeds have made our mind feel guilty. They are breaded

with hope and fear at the same time. And what mostly influences are our former,

but certainly our following deeds as well.

V. Hamlet

Hamlet is the main protagonists in the play “Hamlet”. He is

considered to have whispering conscience before doing the ghastly act. Hamlet’s troubled mind demonstrates the development of an acceptance of

life despite the existence of human evil. It is visible the most in his most

quoted soliloquy:

To

be, or not to be- that is the question:

Whether

'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The

slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or

to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And

by opposing end them…

..Thus

conscience does make cowards of us all (III.1: 57-84)1

Over and over again he struggles to find the right path, to revenge his

father or not, to kill himself or not. He has the action and the pace of the

play in his own hands, and is constantly delaying as if Shakespeare wanted to

embody the anticipation in our real lives. The critical element in this

development is the prince’s recognition of evil in himself. Also, in containing

both good and evil, he represents the dual nature of humankind. The

reconciliation of humanity with its own flawed nature is a central concern.

Actually it is the flawed nature what bothers his conscience the most.

Particularly that is what cuts his freedom of action, although he can deal in a

practical manner with the world of intrigue that surrounds him. Hamlet manages

to direct our attention often to his own concerns, large issues such as

suicide, the virtues and defects of humankind, and the possibility of life

after death. Above all, his circumstances demand that he considers the nature

of evil. He declares that his life is not worth “a pin’s fee” (I.4.65); indeed,

he longs for death, as he declares more than once, wishing “. . . that this too

sullied flesh would melt” (I.2:129) and declaring death “. . . a consummation -

Devoutly to be wish’d” (III.1:63–64)

Many times he considers and then rejects a self-slaughter. Once it is

because of the religious injunction against it and once out of fear of the

afterlife. Towards the end, he still remains calm, coming to terms with the

futility of his philosophical inquiries. Probably that way he found relief for

his inquiring conscience.

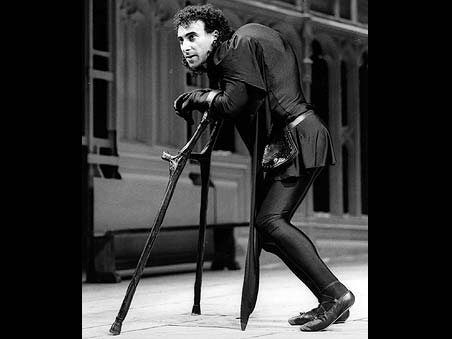

VI. Richard III

Another human duality is represented

in the Richard III. Here the major character Richard is made to be evil representation.

However, when he shows his feelings, we can see that deeply inside him, lays

frustrated and hurt man. Partly it is due to his physical deformity and in the

analogy of that his psychological deformity as well. He rationalizes his

rejection of human loyalties by theorizing that his physical nature has placed

him beyond ordinary relationships. All this leads to his conscious choice to

reject love and brotherhood and to embrace egotism and self-sufficiency. Thus

he can claim, “I am myself alone” (V.6:83). Through his monologues and asides,

he brings the audience into an almost conspiratorial intimacy with him: “O

coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!/...Cold fearful drops stand on my

trembling flesh.”(V.3:179/181) He struggles to suppress the voice of his

conscience, trying to convince himself that there is nothing to be afraid of:

What do I fear? Myself? There's none else by

Richard loves Richard; that is, I am I.

Is

there a murderer here? No-yes, I am.

And his soliloquy continues like a dialogue with his conscience which

triggers hatred and love at the same time inside him:

I am a villain; yet I lie, I am not.

Fool,

of thyself speak well. Fool, do not flatter.

My

conscience hath a thousand several tongues,

And

every tongue brings in a several tale,

And

every tale condemns me for a villain (V.3:191-195)

Yet, the corrupted conscience is that what drives him into all these evil

deeds. Even when he has bad dream and apparitions, he does not want to embrace

the repentance. Eventually, he struggles with the realization that he is an

evil person who is to be punished, although his primary choice was particularly

that- to prove himself a villain.

VII. Macbeth

The third play in this parallel is Macbeth, a play in which, the

duality is not represented only in one person, but symbolically there are two main

protagonists. The aim that Shakespeare had on mind possibly was to give two

people which will complement each other. He achieves that complementation and

further on he achieves to make his point stronger. From two apparently strong

characters, at the end we get two crushed and fallen pieces. Macbeth, the duke

and his wife Lady Macbeth, are tempted and they cannot resist. Macbeth’s weakness is compounded by the urging of the equally ambitious Lady Macbeth

and the encouragement given him by the “Wicked sisters”. One of the play’s

manifestations of the power of evil is the collapse of Macbeth’s personality.

Macbeth commits, or causes to be committed, more than four murders: first, that

of the king, which he performs himself (II.2), and then those of Banquo (III.3)

and of Lady Macduff and her children in (IV.2). His behaviour during and after

each of these events is different, yet Macbeth still retains the moral

sensibility to declare:

“I dare do all that may become a

man.

Who

dares do more is none” (I.7:47-48)

But Lady Macbeth encourages him to

overcome his scruples, and he kills the king (II.2). He is immediately plagued

by his conscience; he tells of how he “could not say ‘Amen’” (II.2: 24) and of

the voices that foretold sleeplessness. His absorption with his bloody hands

foreshadows his wife’s descent into madness (V.1). Nevertheless, he carries his

plot through and is crowned although he is aware that he has put “rancors in

the vessel of his peace” (III.1). The peak of his consciousness prickling is

after the banquet when he sees the ghost of Banquo:

MACBETH.

If I stand here, I saw him.

LADY

MACBETH. Fie, for shame!

MACBETH.

Blood hath been shed ere now, i' the olden

time,

Ere

humane statute purged the gentle weal;

Ay,

and since too, murthers have been perform'd

Too

terrible for the ear. The time has been,

That,

when the brains were out, the man would die,

And

there an end; but now they rise again,

With

twenty mortal murthers on their crowns,

And

push us from our stools. This is more strange

Than

such a murder is (III.4:77- 84)

VIII. Summary

To sum up in all this range

of actions and characters, one thing remains certain, Shakespeare remains

controversial but at the same time so close to human nature and thus close to

us, as if he were our contemporary. The issue of conscience links all these

characters as they all fit into the dual framework of human nature; the battle

between good and evil, the tempting situations and inability to resist them

even when the conscience slaps their minds. As it has been explored here, no

matter how reasonable Hamlet is, or evil Richard is, or mad Macbeth and Lady

Macbeth are, they all fall into their own traps of conscience that drive them

all to tragic end in order to be

sustained the myth of divine providence. Furthermore, punishment reaches them

all in the very moment when they become aware that their conscience is already

corrupted. No matter which behaviour pattern they choose, we come to the

beginning to prove that:

“As each mans minde is

guiltie, so doth he

Inlie breed hope and feare,

as his deeds be.” (Ovid. Fast. i. 485.)

Works

Cited:

1.

Bevington, David, ed. The Complete Works of Shakespeare.

6th Ed. New York: Pearson Education, 2009.

2. Farrell, Kirby, ed. Play, death,

and heroism in Shakespeare. University of North Carolina Press, 1989

3. Florio, John. ed.

Montaigne's Essays: Book II. Chapter V:Of Conscience. The University of

Oregon.1999

4. Foakes, R. A.,

ed. Coleridge's

Criticism of Shakespeare: A Selection By Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Continuum International Publishing

Group, 1989

5.

Larque, Thomas, ed. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lectures and Notes on

Shakspere and Other English Poets London: George Bell and Sons, 1904, pp. 342-368.

No comments:

Post a Comment